Talkin’ Trash

The ocean, one of the vastest and unique environments here on planet Earth. Our oceans cover about 70% of the entire planet

Talkin’ Trash

By: Shelby Schmelzle, Education Program Coordinator

Cape May Whale Watcher

Marine Debris, what is it?

The ocean, one of the vastest and unique environments here on planet Earth. Our oceans cover about 70% of the entire planet, which has allowed humankind to greatly overestimate its ability to store and absorb our trash. When human manufactured material enters into our oceans it is then renamed marine debris. It is defined by NOAA as “any man-made an object that has been discarded, disposed of, or abandoned that enters the coastal or marine environment” (NOAA 2017). Marine debris is one of the most widespread pollution problems facing our world today. It is a worldwide issue and is found in every ocean, on every coastline, and it is making life in the ocean very difficult for many different species.

How does it get there?

Marine debris can enter our oceans one of two ways, directly or indirectly. When it enters the ocean directly it is by ship or fishing boats, essentially it is when the trash enters directly into the oceans without going through other water sources, such as streams or rivers. Indirectly is considered to be more common because these are land-based sources, and the trash enters our oceans through rivers, streams, and storm drains. These land-based sources are the most common forms of marine debris and account for about 80% of all the marine debris in our oceans today.

Top 10 Spielautomaten für deutsche Spieler 2024 von Kasinique

Willkommen bei Kasinique! Heutzutage gibt es eine schier endlose Auswahl an Spielautomaten für deutsche Spieler, die ständig weiterentwickelt und verbessert werden. Doch welche sind die besten und beliebtesten im Jahr 2024? In diesem Artikel präsentieren wir Ihnen die Top 10 Spielautomaten, die bei deutschen Spielern hoch im Kurs stehen und für Nervenkitzel und Unterhaltung sorgen.

Von aufregenden Themen und innovativen Features bis hin zu großzügigen Gewinnchancen und spannenden Bonusrunden - unsere Liste bietet einen Einblick in die Welt der besten Spielautomaten, die derzeit auf dem Markt sind. Egal, ob Sie ein erfahrener Spieler sind oder gerade erst in die Welt der Online-Slots eintauchen, diese Auswahl wird Ihnen helfen, die richtige Wahl zu treffen und Ihr Spielerlebnis auf ein neues Level zu heben. Tauchen Sie ein in die faszinierende Welt der Spielautomaten und entdecken Sie, welche Titel die Herzen der deutschen Spieler im Sturm erobern!

Die besten Spielautomaten-Titel für deutsche Spieler im Jahr 2024

Entdecken Sie die Top 10 Spielautomaten für deutsche Spieler im Jahr 2024 von Kasinique. Mit einer spannenden Auswahl an Spielen bietet Kasinique eine Vielzahl von Optionen für Glücksspielfans. Unter den Top-Spielautomaten ist "Mega Jackpot Madness", ein aufregendes Spiel mit riesigen Gewinnmöglichkeiten. Ebenfalls beliebt ist "Wild Wild West Adventure", das Spieler in eine actiongeladene Welt des Wilden Westens entführt.

Weitere Highlights sind "Treasure Quest", ein Abenteuerspiel mit versteckten Schätzen, und "Lucky Charm Magic", ein mystischer Spielautomat mit magischen Gewinnchancen. Mit hochwertiger Grafik und innovativem Gameplay bieten die Spielautomaten von Kasinique ein unvergessliches Spielerlebnis. Tauchen Sie ein in die Welt der Top 10 Spielautomaten und erleben Sie Nervenkitzel und Unterhaltung auf höchstem Niveau.

Neue aufregende Spielautomaten von Kasinique für deutsche Spieler

Wenn es um Spielautomaten geht, sind deutsche Spieler immer auf der Suche nach den besten Optionen. Bei Kasinique finden Sie eine breite Auswahl an Top-Spielautomaten, die 2024 besonders beliebt sind. Hier sind die Top 10 Spielautomaten für deutsche Spieler bei Kasinique:

- Book of Ra: Ein Klassiker unter den Spielautomaten, der mit spannenden Features und lukrativen Gewinnen überzeugt.

- Starburst: Dieser beliebte Slot von NetEnt begeistert mit leuchtenden Edelsteinen und hohen Gewinnchancen.

- Gonzo's Quest: Tauchen Sie ein in die Welt der Inka mit diesem aufregenden Spielautomaten von NetEnt.

- Mega Moolah: Ein progressiver Jackpot-Slot, der bereits zahlreiche Spieler mit Millionengewinnen belohnt hat.

- Book of Dead: Ägyptische Mythologie und hohe Gewinne erwarten Sie bei diesem spannenden Spielautomaten.

- Immortal Romance: Ein Slot mit Vampir-Thema, der mit fesselnder Storyline und lukrativen Bonusfunktionen begeistert.

- Dead or Alive 2: Dieser Western-Slot von NetEnt bietet hohe Volatilität und spannende Features.

- Bonanza: Ein Slot mit Megaways-Mechanik, der für seine hohe Gewinnmöglichkeiten bekannt ist.

- Legacy of Dead: Tauchen Sie ein in die Welt der Pharaonen und entdecken Sie verborgene Schätze bei diesem Play'n GO Slot.

- Wolf Gold: Ein Slot mit Wild-West-Thema und lukrativen Bonusfunktionen, der für Spannung sorgt.

Entdecken Sie diese und viele weitere aufregende Spielautomaten für deutsche Spieler bei Kasinique. Besuchen Sie noch heute https://kasinique.com/ und tauchen Sie ein in die Welt des Online-Glücksspiels. Viel Spaß und möge das Glück auf Ihrer Seite sein!

Beliebte Spielautomaten bei deutschen Spielern: Die Top 10 für 2024

Entdecken Sie die Top 10 Spielautomaten für deutsche Spieler im Jahr 2024, präsentiert von Kasinique. Diese Auswahl bietet eine vielfältige Palette an unterhaltsamen und spannenden Spielen, die sowohl Anfänger als auch erfahrene Spieler ansprechen.

Zu den beliebtesten Spielautomaten zählt "Mega Moolah", ein Slot mit progressivem Jackpot, der bereits zahlreiche Spieler zu Millionären gemacht hat. Ebenfalls hoch im Kurs steht "Book of Dead", ein ägyptisch inspirierter Slot mit lukrativen Freispiel-Features.

Weiterhin sorgt der Spielautomat "Starburst" für jede Menge Spaß mit seinen leuchtenden Edelsteinen und innovativen Gewinnmöglichkeiten. Fans von klassischen Früchteslots kommen bei "Sizzling Hot Deluxe" auf ihre Kosten, während "Gonzo's Quest" mit seiner Abenteuerthematik und spannenden Bonusspielen überzeugt.

Weitere Highlights der Top 10 Spielautomaten für deutsche Spieler 2024 von Kasinique sind unter anderem "Bonanza", "Immortal Romance", "Fire Joker", "Thunderstruck II" und "Dead or Alive 2". Tauchen Sie ein in die aufregende Welt der Online-Slots und erleben Sie unvergessliche Glücksmomente bei diesen erstklassigen Spielen.

Entdecken Sie die spannendsten Spielautomaten von Kasinique für das Jahr 2024

Entdecken Sie die Top 10 Spielautomaten für deutsche Spieler im Jahr 2024 von Kasinique. Diese Auswahl bietet eine Vielzahl von aufregenden Spielen, die sowohl Anfänger als auch erfahrene Spieler begeistern werden. Unter den beliebtesten Spielautomaten finden sich Titel wie "Mega Fortune Dreams", bekannt für seine progressiven Jackpots, sowie "Book of Dead", ein Slot mit spannendem Ägypten-Thema und lukrativen Freispielrunden.

Weitere Highlights der Liste umfassen "Starburst", ein klassischer Slot mit funkelnden Juwelen und hohen Gewinnchancen, sowie "Gonzo's Quest", ein Abenteuer-Slot mit einzigartigem Avalanche-Feature. Spieler können sich auch auf "Bonanza" freuen, einen Slot mit Megaways-Mechanik, die für Tausende von Gewinnmöglichkeiten sorgt. Mit diesen und weiteren spannenden Spielautomaten garantiert Kasinique ein unvergessliches Spielerlebnis für alle Casino-Fans in Deutschland.

Kasinique präsentiert die Top 10 Spielautomaten für deutsche Spieler im Jahr 2024

Willkommen bei Kasinique! Hier sind die Top 10 Spielautomaten für deutsche Spieler im Jahr 2024. Unsere Auswahl umfasst eine Vielzahl von spannenden Spielen, die garantieren, dass Sie stundenlangen Spielspaß erleben werden. Von klassischen Früchteslots bis hin zu aufregenden Videospielautomaten, hier ist für jeden Geschmack etwas dabei.

1. Book of Ra Deluxe: Ein beliebter Slot mit einem ägyptischen Thema und lukrativen Bonusrunden. 2. Starburst: Ein Klassiker mit funkelnden Edelsteinen und hohen Gewinnchancen. 3. Mega Moolah: Der berühmte Jackpot-Slot mit progressiven Gewinnen. 4. Gonzo's Quest: Ein Abenteuerslot mit innovativem Gameplay und tollen Animationen. 5. Immortal Romance: Ein Vampir-Themenslot mit fesselnder Storyline. 6. Bonanza: Ein Megaways-Slot mit explosiven Gewinnmöglichkeiten. 7. Thunderstruck II: Ein Slot mit nordischem Thema und vielfältigen Bonusfunktionen. 8. Dead or Alive 2: Ein Western-Slot mit hohem Volatilitätsfaktor. 9. Jammin' Jars: Ein fruchtiger Slot mit Cluster-Gewinnen. 10. Fire Joker: Ein klassischer Slot mit modernem Twist und hohen Auszahlungen.

Wir hoffen, dass dieser Überblick über die Top 10 Spielautomaten für deutsche Spieler im Jahr 2024 von Kasinique Ihnen dabei geholfen hat, die aufregendsten und lukrativsten Spiele zu entdecken. Mit einer Vielzahl von Themen, Features und Gewinnmöglichkeiten bieten diese Spielautomaten ein erstklassiges Spielerlebnis für alle Casino-Enthusiasten. Egal, ob Sie ein Fan klassischer Fruchtmaschinen oder moderner Video-Slots sind, in dieser Auswahl ist für jeden etwas dabei. Tauchen Sie ein in die Welt des Online-Glücksspiels und erleben Sie Nervenkitzel und Spaß bei diesen herausragenden Spielautomaten!

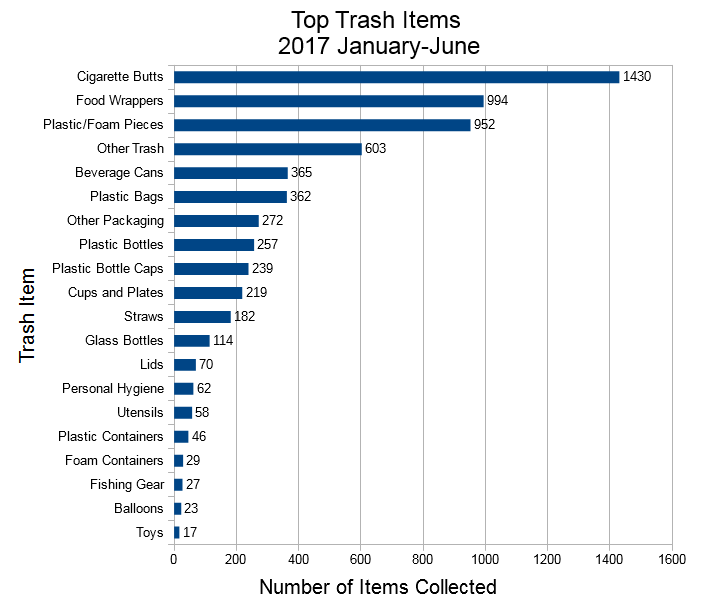

Image 2: the various types and quantities of marine debris found by the University of Florida during their beach cleanups last year from January-June (bay.ifas.ufl.edu).

Where does it go?

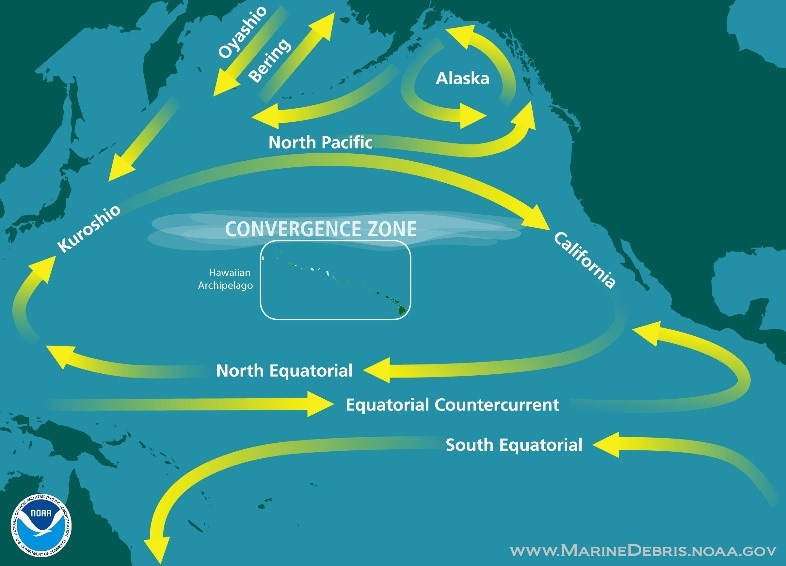

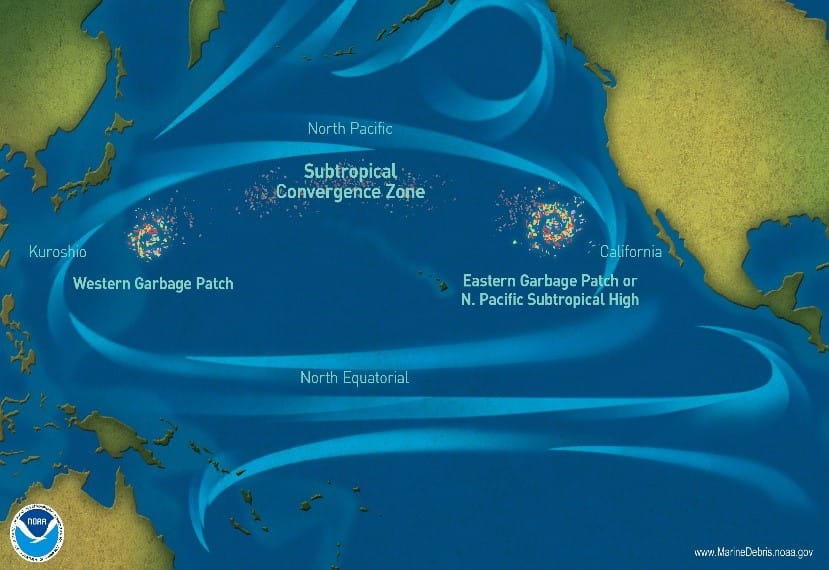

The movement of ocean water is greatly dependent on ocean currents, gyres, and wind. Once marine debris enters our oceans it can travel hundreds if not thousands of miles from its original entry point by entering these currents, making it extremely difficult to know exactly where a specific piece of marine debris originated from. Along with moving marine debris, these ocean currents and gyres can also create areas of debris accumulation, known as accumulation zones or often referred to as garbage patches (NOAA 2017). The most well-known garbage patch is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch out in the Pacific Ocean. No one knows how large this garbage patch is because its size and content are constantly changing due to our ocean currents, but it is one of the largest patches of marine debris in our oceans today.

Image 3: the currents in the Pacific Ocean (left) and the location of the great pacific garbage patch in the Pacific Ocean (right) (NOAA 2017).

Dangers to Wildlife

Marine debris is a huge hazard that animals in the ocean have to face almost every day. There are three main ways that marine debris is dangerous to wildlife: entanglement, ingestion, and disruption of natural habitats. One of the most recognized impacts of marine debris on wildlife is entanglement. This is when marine debris like fishing gear, six-pack rings, balloon strings, and more become entangled around an animal, which can lead to injury, starvation, suffocation, and even death. Marine debris entanglements have been documented for more than 275 species of animals, including 46% of all species of marine mammals (California Coast Commission, 2017). Along with entanglement, many marine animals have been known to ingest marine debris. The debris is usually mistaken for food, an example being sea turtles eat jellyfish but might mistake a plastic bag for one because of their similar appearance. When animals consume marine debris it can make them feel full without gaining any nutrients, which may eventually lead to starvation. Along with starvation, consuming marine debris can lead to internal injury and internal blockages, which can lead to death. Lastly, marine debris can provide a method of transport for organisms throughout our oceans. Organisms attach themselves to the marine debris and get transported to a new habitat. A 2002 study of 30 remote islands throughout the world showed that marine debris more than doubled the "rafting" opportunities for species (Barnes 2002). All of these invasive species can hurt the natural populations of animals in the habitat they are transported to.

Image 4: a sea lion pup and green sea turtle entangled in fishing line (NOAA 2017).

Dangers to People

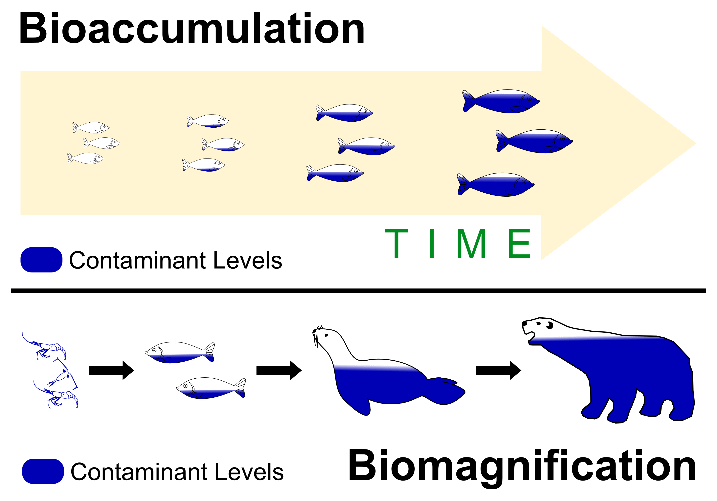

Along with wildlife, marine debris has a negative effect on humans in many ways as well. We all enjoy spending the day at the beach, but dangerous debris such as glass and needles can harm humans physically. When we increase the amount of debris in our waterways we also increase the number of harmful chemicals and pathogens in our water, greatly diminishing water quality in many areas. Also, a lot of the seafood we consume can contain debris. A study of predatory fishes in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre found that 19% of the individuals contained marine debris, most of it plastic, this included species commonly eaten by people (Choy 2013). When consumed, plastic debris can concentrate and transport chemicals into and through the marine food chain, which in turn gets transported to us when we consume seafood containing these pollutants.

Image 5: Bioaccumulation: the concentration and transport of dangerous chemicals in the marine food chain. (Olenick 2013).

There are many ways an individual can help with the issue of marine debris, starting with keeping our beaches clean. When you go to the beach be sure to clean up and dispose of all the trash you bring with you and that you find. Remember, leave only footprints! Also, pick up and dispose of trash you find in your neighborhood, school, or local park, in doing this you will greatly reduce the amount of trash that ends up in our waterways and in our oceans. Make sure you follow the 4R’s, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, and Refuse. Instead of using single-use plastic, switch to reusable products such as reusable water bottles and cloth shopping bags. Be a smart shopper, purchase items made with recycled materials or have little to no packaging. Choose natural materials over more synthetic materials. Lastly, get involved, organize a beach cleanup, volunteer at a cleanup day, donate to organizations that are cleaning up our oceans and educating people on this issue.

How you can help

References:

Barnes D.K.A., 2002. Invasion by marine life on plastic debris. In: Nature 416, 808-809

California Coast Commission. (2017). The Problem With Marine Debris. Retrieved from https://www.coastal.ca.gov/publiced/marinedebris.html

Choy, C. A. Drazen, J. C., 2013. Plastic for dinner? Observations of frequent debris ingestion by pelagic predatory fishes from the central North Pacific. In: Marine Ecology Progress Series Vol. 485, 155-163.

NOAA. 2017. What is marine debris? Retrieved from https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/marinedebris.html

NOAA. 2017. How Marine Debris is Impacting Marine Animals and What You Can do About it. NOAA Office of Response and Restoration Blog. Retrieved from: https://blog.response.restoration.noaa.gov/how-marine-debris-impacting-marine-animals-and-what-you-can-do-about-it

Olenick, Laura. 2013. The Cautionary Tale of DDT – Biomagnification, Bioaccumulation, and Research Motivation. Sustainable Nano. Retrieved from: http://sustainable-nano.com/2013/12/17/the-cautionary-tale-of-ddt-biomagnification-bioaccumulation-and-research-motivation/